Interactions Between Natural Nuclear Reactors and Microbial Evolutionary Processes

Abstract

The impact of ionizing radiation on genetic change is well established, yet the extent to which naturally occurring radiation fields have influenced evolutionary trajectories remains incompletely understood. This study examined correlations between microbial evolution and the radiation and geochemical environments associated with natural fission reactors, with emphasis on the Oklo–Bangombé system in present-day Gabon, Africa. The current paper compares plausible doserate regimes adjacent to reactor zones with published observations of radiationinduced phenotypes, geneexpression changes, and repair strategies in model organisms and complex biotas. This study further considers indirect mechanisms (e.g., water radiolysis, redox restructuring, tracemetal mobilization) by which natural reactors could have modulated ecological selection pressures over long timescales. The synthesis supports the plausibility of three interacting pathways: (i) increased mutation supply under low, chronic dose rates; (ii) selection in oxidantrich, redoxstratified niches; and (iii) metabolic subsidies (e.g., H₂) from radiolysis that support chemotrophic guilds. Although temporal–spatial associations exist between reactor activity and biological innovations preserved in Paleoproterozoic strata of Gabon, current evidence remains correlational rather than demonstrably causal. The study further outlines testable predictions and experimental designs capable of discriminating among these mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Anubha Bajaj, Consultant Histopathologist, A.B. Diagnostics, Delhi, India

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2026 Chuck Easttom.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Citation:

Introduction

Natural nuclear reactors, first predicted by Kuroda and recognized at Oklo in present-day Gabon, Africa in 1972, provide a unique window into systems where selfsustaining fission occurred without human engineering 1. Approximately two billion years ago the isotopic composition of uranium contained a sufficiently high fraction of 235U to enable moderated chain reactions in watersaturated ore bodies. The reactor zones at Oklo and Bangombé (present-day Gabon) operated episodically, with negative thermal–hydrologic feedback that limited power excursions and produced cyclic behavior 2, 3, 4.

The relationship between natural nuclear reactors, such as the one found in Oklo, and biological evolution is subtle, but it highlights how natural nuclear processes may have influenced the planet’s chemistry, radiation environment, and possibly even the pace of biological change over geological time. Ionizing radiation from uranium deposits or other natural fission events can cause DNA mutations 5. While excessive radiation is harmful, low-level exposure over geologic timescales may have contributed to genetic variability, which is a driving force of evolution. The chemical byproducts of natural fission (e.g., redox conditions) could have influenced elemental availability 6, potentially impacting early microbial metabolisms dependent on redox gradients.

The potential evolutionary significance of such systems lies in their ability to reshape both radiation and geochemical landscapes. Ionizing radiation is a potent mutagen capable of inducing single and doublestrand DNA breaks, base damage, and chromosomal rearrangements; at sublethal, chronic levels it can increase mutational input that selection acts upon 7, 8. Beyond direct DNA damage, radiolysis of water produces oxidants and molecular hydrogen, potentially intensifying redox gradients that are central to microbial metabolism. The Paleoproterozoic Francevillian Basin, formed at the same time that the Oklo natural reactors were active, preserves oxygenated shallowmarine settings juxtaposed with anoxic deeper waters, conditions conducive to strong chemical gradients and diverse microbial guilds 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Radiation and Genetic Change

Ionizing radiation (α, β, γ, and neutron fields) damages DNA both directly, via energy deposition in macromolecules, and indirectly through reactive oxygen species generated by water radiolysis. Dose is measured in gray (Gy, J·kg⁻¹), while risk to organisms is often expressed in sievert (Sv) to account for radiation weighting and tissue responses. High acute doses are deleterious, yet low to moderate chronic dose rates can provoke adaptive molecular responses and, over long intervals, may modulate evolutionary tempo 8, 7.

One example of the impact of radiation on genetics can be observed in moderate X-Ray exposure. Experiments in human cell lines demonstrate that relatively modest Xray exposures can reprogram gene expression. In HT29 colorectal cells, singlefraction doses as low as 0.1 Gy upregulated CD44, ALDH1, and Oct4, markers associated with stemness and plasticity 15. Although these are mammalian cancer cells, the finding illustrates a general principle: lowdose irradiation can shift regulatory networks and phenotypes.

Soleymanifard et al. (2021) used HT-29 colorectal cell line, obtained from the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France. The HT-29 cells were plated in a 12.5 cm2 tissue culture flask. The cells were then irradiated with various single doses of X-rays including 0.1, 2.5, 5, and 10 Gy, which was emitted from an X-ray unit (Philips, serial number 2.625, Netherland, dose rate: 1.365 Gy/min with 100 kVp and 8 mA) at room temperature. Non-radiated cells were used as a control group. The results of this study indicated that different doses of X-ray may effectively upregulate the expression of CD44, ALDH1, and Oct4 genes, all of which play a role in Cancer Stem Cells “CSC” induction in colorectal cancer cells. These results suggest that even low-dose irradiation can upregulate gene expression. While inducing cancerous cells is a deleterious outcome from radiation, this study does demonstrate that even low doses of radiation can alter gene regulation

Other examples of the impact of radiation on genetic change can be found at Chernobyl, Ukraine. Mortazavi et al., (2025) conducted a literature survey regarding the biological impact of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster on the local biome. This survey showed that while there were certainly severe deleterious effects from acute exposure to the radiation of Chernobyl, some species had adaptive outcomes. One study mentioned in this survey was on Eastern tree frogs (Hyla orientalis)16. These frogs, now referred to as “Chernobyl black frogs”, have a developed a darker, nearly black coloration. The increased melanin content in their skin serves as an adaptive function. The melanin absorbs and disperses radiation energy, thereby providing an additional layer of cellular protection against the harmful effects of radiation. This survey, however, did provide indicators of positive effects from increased background radiation.

Daly (2023) studied the bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. This bacterium is a spherical, pink–red bacterium discovered in 1956 when it survived sterilization by intense gamma radiation during canned food experiments. Scientists realized it could tolerate radiation doses far beyond anything previously observed. These bacteria are noteworthy because they can survive 5,000 – 15,000 Gy (500,000 to 1,500,000 rads) of ionizing radiation. By comparison, a dose of 2 – 10 Gy received in a short period cause death in 50% of cases for humans 7. Daly (2023) discussed the role of homologous recombination in the radiation tolerance of D. radiodurans, highlighting the extremes that adaptability can reach.

Other studies have focused on the role of radiation in the development of prebiotic chemistry. Ershov (2022) argues that radioactive decay, primarily from isotopes ⁴⁰K, ²³⁵U, ²³⁸U, and ²³²Th, as a major driver of prebiotic chemistry on early Earth. Radiation split seawater into reactive radicals, which then converted dissolved volcanic gases (such as CO, HCN, CH₄, and NH₃) into amino acids, sugars, nucleobases, and other key organic compounds. At the same time, water radiolysis generated significant amounts of oxygen long before photosynthesis emerged. Over hundreds of millions of years, this process accumulated organic matter, purified the oceans from toxic compounds, and helped create the chemical conditions necessary for early life to emerge.

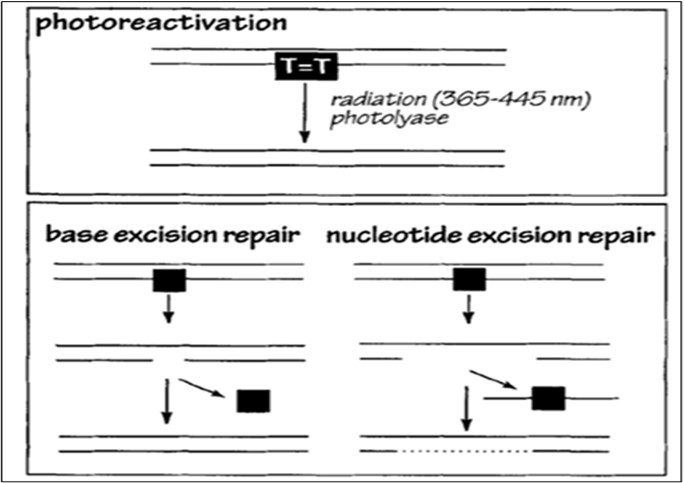

Even the more common ultraviolet (UV) radiation can have a role in genetic change. Rothschild (1999) published a comprehensive analysis of how UV radiation has shaped the evolutionary trajectories of protists, emphasizing its dual role as both a mutagenic force and a powerful selective agent. Rothschild argues that because early Earth lacked a substantial ozone layer, primitive eukaryotes and protistan lineages were exposed to significantly higher UV fluxes, particularly UVA, UVB, and UVC, than those experienced under modern atmospheric conditions. A major focus of the Rothschild study was the molecular basis of UV-induced DNA lesions, including: Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs); (6-4) photoproducts; and DNA–protein crosslinks and strand breaks. These forms of damage are illustrated in the DNA repair diagrams on page 550 (Figure 3 in the Rothschild paper; Figure 1 in this paper), which depict photoreactivation, base excision repair, and nucleotide excision repair.

Figure 1.DNA Damage Repair Mechanisms from the Rothschild paper.

Rothschild further emphasized that the capacity for efficient DNA repair, especially photoreactivation by photolyase and various excision pathways, has been both a functional necessity and an evolutionary driver, influencing genome stability and mutation rates in diverse protistan taxa 17. Rothschild concludes that UV radiation has been a pervasive and potent evolutionary force in protistan history, acting through direct mutagenic effects on DNA; Selection for robust DNA repair systems; physiological and behavioral adaptations that mitigate UV exposure; and selective pressures shaping the evolution of photosynthesis and sexual reproduction

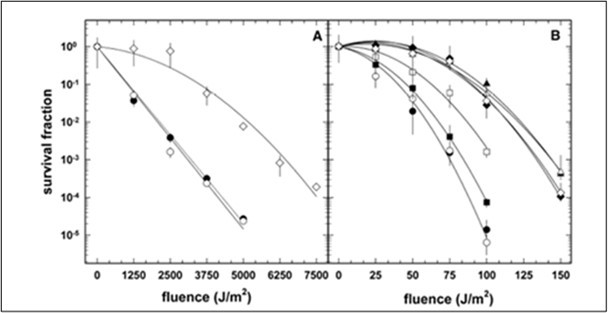

Wassmann et al. (2010). investigated the evolutionary capacity of Bacillus subtilis to adapt to ultraviolet (UV) radiation levels modeled after the Archean eon, when Earth lacked a protective ozone layer and surface environments were exposed to intense fluxes (i.e., 200–400 nm). Using an experimental evolution design over ~700 generations, the authors subjected B. subtilis populations to repeated cycles of high-intensity polychromatic UV exposure. Populations exhibited a pronounced and heritable increase in UV resistance, approximately a 3–4Xelevation in UVC tolerance relative to the ancestral strain. As shown in survival curves on pages 7–8 (Wassmann et al Figure 2, Figure 2 in this paper), the acquisition of UV resistance occurred in discrete evolutionary steps, suggesting cumulative beneficial mutations.

Figure 2.Survival Curves of B. subtilis cells in the Wassmann et al. paper.

In addition to enhanced UV tolerance, the evolved strain (MW01) demonstrated cross-protection against several abiotic stressors, including ionizing radiation, oxidative stress, salinity, and desiccation, with particularly striking increases in X-ray resistance (up to 7X; see Wassman et al. Figure 5 on page 10) and short-term desiccation survival (see Wassman et al. Figure 4 on page 9). These changes imply that chronic UV stress selects not only for improved DNA repair and stress-response pathways but also for generalized physiological robustness. The findings support the hypothesis that early microbial life exposed to Archean-level UV radiation could have rapidly evolved elevated resistance, and they offer mechanistic insight into how environmental UV regimes may have shaped microbial evolution on early Earth and potentially on other planetary bodies.

The evidence is quite clear: radiation, while it can have deleterious effects on the biome, can also be a driving factor in genetic change as well as a natural selective agent. The evidence shows radiation playing a substantial role in biological evolution. This role appears to be more pronounced in simpler organisms such as Protista, Archaea, Fungi, and Bacteria.

Natural Reactors

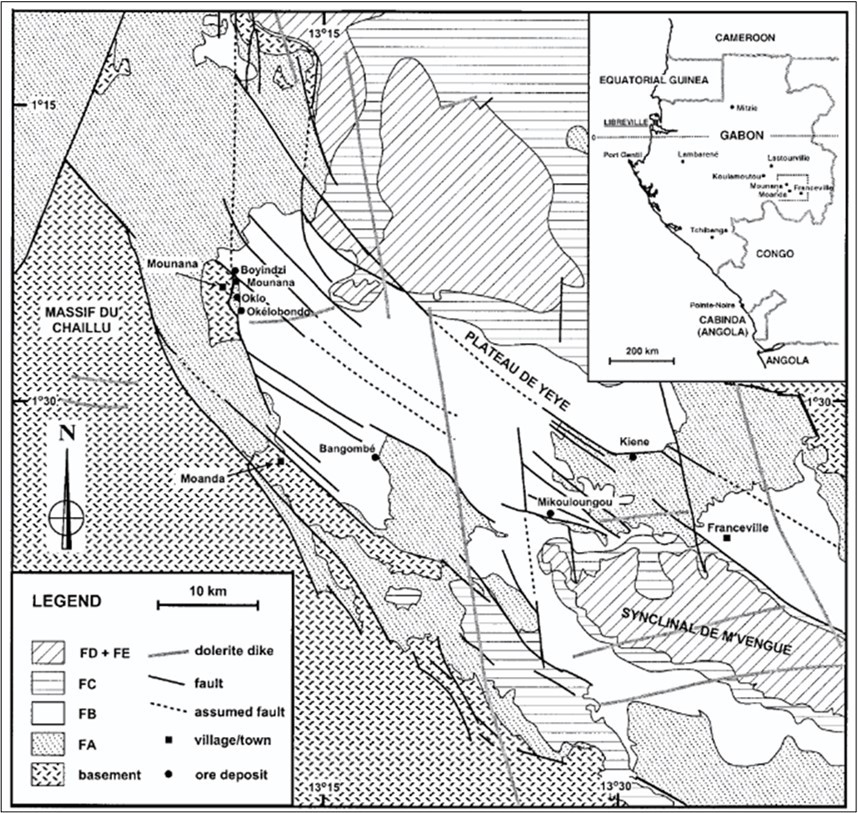

The conditions under which a natural nuclear reactor could exist had been predicted in 1956 by Paul Kazuo Kuroda 18. The phenomenon was discovered in 1972 in Oklo (Figure 3) by French physicist Francis Perrin under conditions very similar to what was predicted 1. Natural fission reactors are uranium deposits where self-sustaining nuclear chain reactions occur spontaneously 3. Around 1.7 billion years ago, conditions in the uranium-rich sedimentary rock formations of the Oklo region were conducive to sustaining a chain reaction. At that time, the concentration of U-235 (a fissile isotope of uranium) in natural uranium was higher than it is today. Water acted as a moderator, slowing down neutrons and allowing the reaction to sustain itself. The reactor operated intermittently for around 150,000 years. Periodically, water would flood the reactor, acting as a neutron absorber and halting the chain reaction. When the water receded, the reaction would resume. The reactor exhibited a form of self-regulation. As the chain reaction progressed, heat generated would boil away the water, slowing the reaction. Conversely, as the reactor cooled, water would return, allowing the reaction to restart. Rare earth elements also played a role as neutron absorbers 19. Figure 3 in the current paper is Figure 1 from Jensen, & Ewing (2001).

Figure 3.The Gabon Region of Africa from Johnson and Ewing

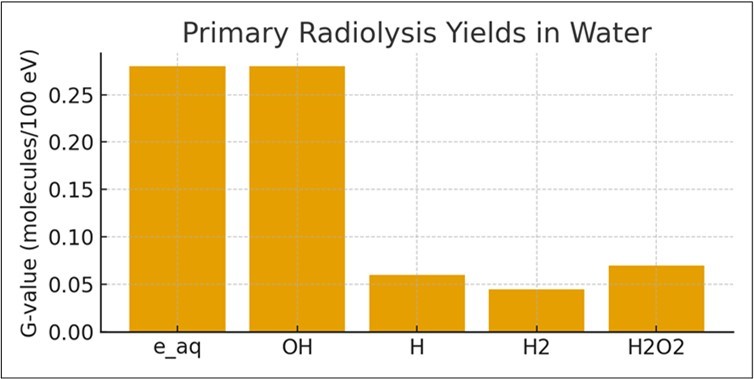

Ionizing radiation splits water into reactive species 20. Primary yields include hydrated electrons, hydroxyl radicals, and molecular hydrogen. H₂ accumulation supports hydrogenotrophic metabolisms while oxidants restructure Fe–S–Mn redox systems 9. Ionizing radiation interacts with water to produce a complex suite of reactive species. Figure 4 demonstrates radiolysis yields in water.

Figure 4.Radiolysis yields in water

The radiolytic yield (G-value) of H₂ in reactor-proximal groundwater could reach 0.4–0.6 molecules per 100 eV of deposited energy. Over extended periods, this accumulated H₂ forms a potent reducing agent usable by hydrogenotrophic microbes 21. Meanwhile, oxidants such as H₂O₂ and OH structurally modify Fe-, Mn-, and S-bearing minerals, creating steep redox gradients. These gradients would have substantial ecological implications through processes such as enhanced Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycling; expanded niches for sulfide oxidizers and reducers; increased trace-metal mobility relevant to early eukaryotic physiology; and persistent chemical energy supply independent of photosynthesis 22, 23.

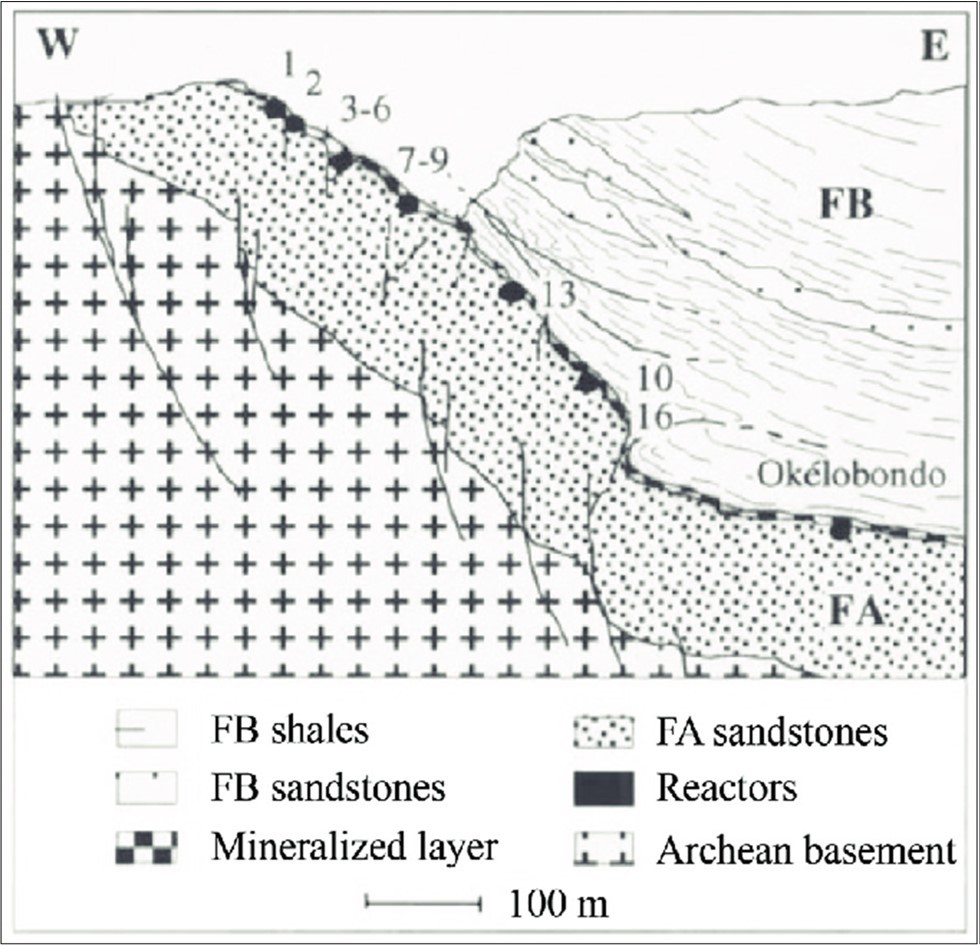

The Oklo region contains 16 separate sites (Figure 5) where self-sustaining natural reactions are believed to have occurred 1.7–2.1 billion years ago during the Paleoproterozoic era. The fission of uranium in the reactors produced various isotopes and elements, including xenon, krypton, and other fission products. The unique isotopic signatures of these elements served as evidence of past nuclear reactions 24. Over time, the reactors gradually consumed their fissile fuel, and the water content changed, eventually leading to the cessation of chain reactions. Today, the natural reactors are dormant, serving as a natural laboratory for studying nuclear physics and geology. Figure 5 shows the Oklo reactors, and is from Geckeis, Salbu, Schafer, & Zavarin (2019).

Figure 5.Geckeis, Salbu, Schafer, & Zavarin (2019) Cross section of the Oklo and Okélobondo deposit area with locations of natural reactor zones.

Each of the 16 known reactor zones (most notably Oklo Zone 2 and Okélobondo) operated at an average thermal power of approximately 100 kilowatts (kW), which is comparable to a small modern research reactor. The total thermal power of all zones combined is estimated to have been on the order of 500 kW – 1 megawatt (MW), depending on groundwater moderation and uranium concentration cycles. The fission rate during active periods was approximately 10¹⁸ to 10¹⁹ fissions per second, releasing roughly 200 MeV per fission or approximately 3×10⁻¹¹ joules per fission.

The estimated thermal neutron flux during operation was 10¹³ – 10¹⁴ neutrons/cm²·s. By comparison a modern power reactor core has fluxes around 10¹⁴ to 10¹⁵ n/cm²·s. Thus, the Oklo natural reactor operated at levels comparable to small modern reactors, though intermittently. The gamma radiation released was on the order of 10⁴–10⁶ Gray/hour (Gy/h) inside the core. At distances of < 100 m, the radiation level would have dropped to approximately 10–100 mGy/h, depending on rock shielding and water presence. For context, 1 mGy/h sustained is about 1,000X higher than the modern background radiation level on Earth (~0.1 μGy/h). The Oklo reactors were not continuously active, rather they cycled on cycles of approximately 0.5–3 hours.

The Bangombé natural reactor is one of the reactor zones in the Oklo area. While the main Oklo site contains about 16 reactor zones, Bangombé is noteworthy because it is younger and is located less than 20 kilometers from the other reactors 4. All of the Oklo reactors follow a similar cycle with three primary steps:

1. Water seeped in → moderated neutrons → fission started

2. Fission heated water → water boiled away → reaction stopped

3. Cooled down → water returned → reaction restarted

The Oklo reactor cycle mimics that of a typical reactor. Water is often used to facilitate reactions in man-made reactors and serves that same role in natural reactors 25. Most fissile nuclei (e.g., U-235) are far more likely to undergo fission when hit by slow, thermal, neutrons. However, neurons released from fission start out fast (~2 MeV). Water solves this by slowing neutrons through elastic scattering due to three processes: (1) hydrogen in H2O has almost the same mass as a neutron, (2) collisions with hydrogen transfer kinetic energy efficiently, and (3) many neutrons become “thermal” after approximately 20–30 collisions ) 26. For natural reactors, once the reaction has begun the heat from fission, eventually causes the water to dissipate, stopping the reaction. Once the rock had sufficiently cooled, water returned and the reaction began again. This produced a nearly periodic 3-hour cycle with approximately 30 minutes critical (on) and approximately 2.5 hours dormant (off).

Microbial Evolution

The Gabon region has been proposed as a cradle for notable eukaryotic innovations, including the earliest evidence for organismal motility in oxygenated shallowmarine settings 27, 12, 28, 29, 30. While radiation at high doses is unequivocally harmful, low, chronic exposures can elevate mutation rates and select for stressresponse pathways. In experimental and natural contexts, organisms demonstrate a spectrum of outcomes ranging from injury to adaptation 16, 31, 32, 15, 7. These outcomes motivate evaluating whether Okloadjacent radiation fields and the associated redox geochemistry, which could have modulated the tempo and mode of early eukaryotic and microbial evolution.

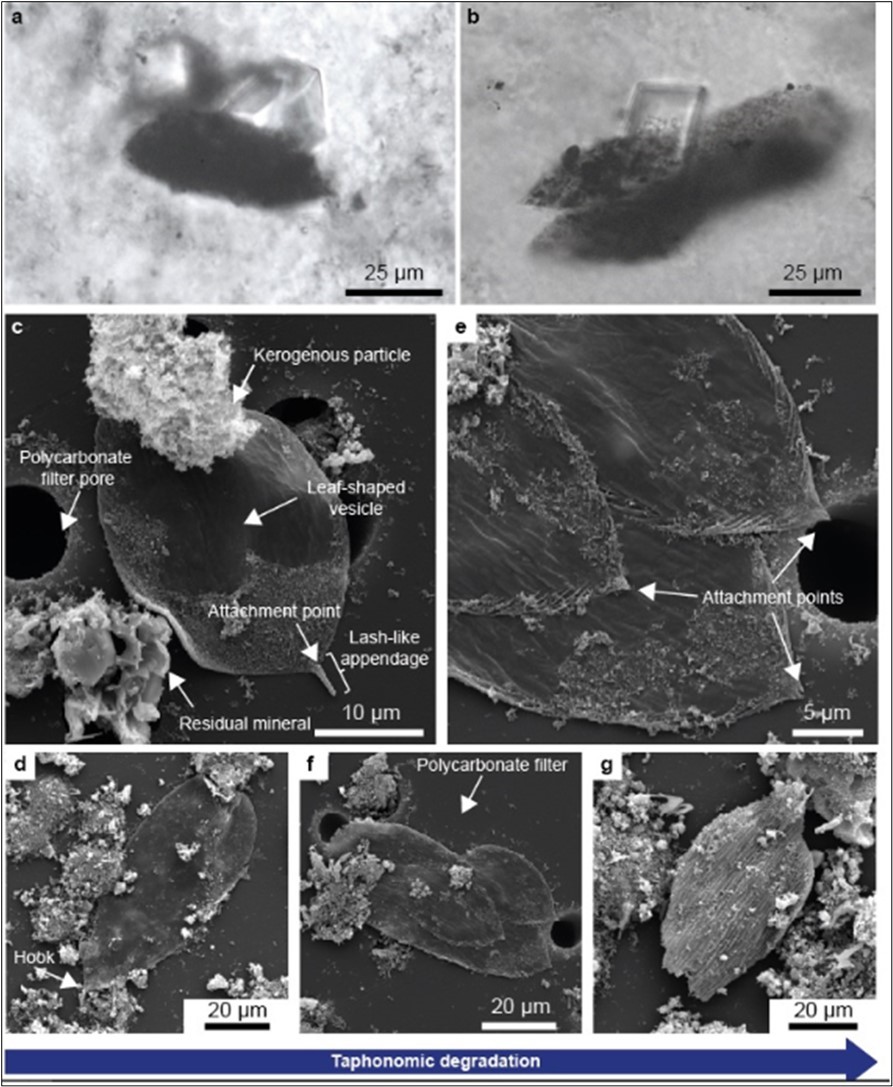

The Oklo region is also believed to be the site where eukaryotes developed motility 28, 30. Micrographs from the Delarue et al., study (2020) showing vesicles presenting a locomotory organelle composed of an attachment point and of a lash-like appendage are provided in Figure 6.

Figure 6.Micrographs from Delarue et al.

This Oklo site is also important for a range of other substantial advances in eukaryotic evolution. Donoghue & Antcliffe (2010) examine microfossils that have morphologies suggestive of coordinated growth and organization. The authors suggest that these may represent some of the earliest evidence for organized multicellularity. Other studies also argue that the site provides some of the earliest evidence for large, organized, likely multicellular life, potentially associated with early eukaryotic biology and oxygen-enabled ecological complexity 12. Porter & Riedman (2023) provide a conceptual and interpretive framework for understanding early eukaryotic fossils that is used to assess sites like Oklo/Francevillian, clarifying what features support eukaryotic affinity versus alternative explanations. These studies demonstrate a least a strong correlation between the Okla site and early advances in evolutionary biology. This correlation suggests that low levels of radiation from natural fission reactors may have played a role in key stages in eukaryotic evolution. Radiation can certainly be a source of mutations, but excess radiation is deleterious to the organism in question (Mavragan, et al., 2019).

Microbial Evolution in the Gabon Region

The Francevillian Group (formations FA–FE) in southeastern Gabon preserves unmetamorphosed siliciclastic and shale successions deposited roughly 2.3–2.0 Ga (with widely cited fossiliferous intervals ~2.14–2.06 Ga). This basin is unusually important because it brackets the Great Oxidation Event and the long positive Lomagundi–Jatuli carbonisotope excursion, when atmospheric and shallowmarine oxygen levels rose 11. The FB2 Member (part of the Francevillian B Formation) hosts abundant microbial textures and the controversial macrofossils (“Francevillian biota”). The FC strata bear stromatolites with microfossils 14. Shallow settings were intermittently oxygenated, while deeper water remained anoxic, a key redox structure that shaped microbial ecosystems.

The FB2 shallowmarine sandstones and siltstones preserve exceptional microbially induced sedimentary structures (MISS) and thin mat laminae (0.2–3 mm), including “elephantskin” textures, wrinkle marks, Kinneyia patterns, domal buildups, discoidal colonies, and pyritized mat patches. Textures and geochemistry point to Cyanobacteriadominated mats 9. Geochemical proxies (e.g., Fespeciation, Mo–U–V, C–N isotopes) indicate an oxygenated photic zone on the shelf, repeatedly renewed by upwelling of nutrientrich anoxic water from depth. This sustained high primary productivity in mats without fully oxygenating the whole basin.

In addition to mats, the FC Formation also preserves a “Gunflinttype” assemblage of microfossils hosted in shallowwater stromatolites (~2.14–2.08 Ga), including filamentous and coccoidal forms that inhabited mildly oxygenated niches 33. Centimeterscale lobate, discoidal, and ribbonlike structures occur in FB2 black shales, commonly pyritized and preserved as discrete individuals beneath an oxygenated water column in deltafront to shelf settings 11, 12. Some beddingplane networks have been interpreted as tracelike structures suggestive of motility. Alternative interpretations suggest bacterial colonies, diagenetic concretions, or pyritegrowth pseudofossils. Recent traceelement and Znisotope data have been viewed by some authors as compatible with eukaryotelike physiology, whereas critical reviews place the earliest robust eukaryote fossils closer to 1.65–1.6 Ga and emphasize caution 29. Taphonomic studies highlight organic–mineral interactions as key to preservation 14. Regional syntheses additionally connect the geology around natural reactors with hypotheses regarding early eukaryote habitats 30.

Centimeterscale, threedimensionally preserved lobate, disk and ribbonlike structures occur in FB2 black shales, commonly pyritized and arranged as discrete individuals. They occur beneath an oxygenated water column in a deltafront to shelf setting. Some beddingplane networks have been interpreted as tracelike structures (possible motility). One view sees colonial organisms with coordinated growth, potentially eukaryotic (or at least sophisticated multicellularity) while others have argued that they are bacterial colonies, diagenetic concretions, or pseudofossils (pyrite growth). Recent traceelement and Znisotope studies, notably unusual Zn enrichment and light Zn isotopes, have been taken by some as consistent with eukaryotelike physiology, but leading reviews remain cautious—placing the earliest robust eukaryote fossils closer to 1.65–1.6 Ga.

Analysis

Experimental evidence from modern taxa and communities (e.g., Deinococcus, Bacillus subtilis, Chernobyl biota) demonstrates that organisms exposed to persistent radiation evolve increased resistance and, in some cases, physiological innovations. In Paleoproterozoic environments, such dynamics may have acted over geological timescales, influencing the rise of early eukaryotic-like traits observed in the Francevillian biota. A rigorous causal link between natural reactors and evolutionary innovation requires the convergence of four conditions:

1. Chronological overlap. Reactor operation in the Oklo district spans ~1.7–2.1 Ga, overlapping with deposition of Francevillian strata with complex microbial ecosystems and putative motile macrostructures 11, 12, 13. This establishes temporal plausibility.

2. Spatial proximity and exposure gradients. Order-of-magnitude dose-rate estimates indicate that outside the ore bodies, chronically irradiated habitats would have experienced exposures on the order of mGy·h⁻¹ or less, influenced by local hydrology and shielding. Such spatial gradients could have shaped microbial ecosystems by creating protected microenvironments—such as pore spaces or microbial mats within permeable sandstones, capable of supporting persistent, sublethal radiation exposure.

3. Mechanistic pathways. There are three primary effects: (i) Direct genetic, with increased mutation input and selection under oxidative stress 7, 8; (ii) physiological/biochemical, via induction of stress responses and repair networks analogous to those observed experimentally 15, 31 and (iii) geochemical,: through radiolysisderived H₂ and oxidants, plus tracemetal cycling, creating persistent redox energy gradients for sulfur, iron, and nitrogencycling guilds documented in Francevillian facies 9, 10. Longterm retention of fission products within mineral matrices suggests localized, reducing conditions favorable for the preservation of biosignatures 34, 35.

4. Modeling and naturalexperiment analogues. Neutronic and geochemical models of Oklo behavior 3, 36, 37 enable firstorder estimates of energy deposition and dose fields. Independent natural experiments (e.g., Chernobyl biota, melanism in H. orientalis) show that adaptation to chronic radiation can occur but is taxon and contextdependent 16, 32.

There are several testable predictions, including: (a) enrichment of stressresponse and DNArepair signatures in molecular clocks of lineages inhabiting reactorproximal facies, (b) spatial covariation between MISS/macrofossils and mineral/elemental indicators of radiolysisenhanced redox cycling, and (c) distinctive mutation spectra under controlled microcosm exposures that reproduce Oklolike dose rates (submGy·h⁻¹ to ~10 mGy·h⁻¹) across many generations, with hydrologic cycling to simulate on–off reactor pulses. Such experiments would directly address causality currently unresolved in the geological record.

Shukla, Tvavc, and Sghaier (2024) conductd a survery of ow microorganisms survive, adapt, and function under ionizing radiation (IR) stress. Among other things, the authors concluded that studying microorganisms in radioactive environments not only deepens understanding of life’s resilience but also has practical implications for biotechnology, environmental remediation, nuclear safety, and astrobiology

Conclusions

There is a large volume of published work that demonstrates that organisms can adapt to radiation under certain chronic exposure regimes (e.g., melanism in H. orientalis near Chernobyl and extreme resistance in D. radiodurans), while other taxa exhibit neutral or detrimental outcomes 16, 32, 31. In Gabon, there is a spatiotemporal correlation between reactor activity and intervals recording increased ecological complexity, including putative motility, in Francevillian strata. The Oklo–Bangombé reactors plausibly influenced local biota by elevating mutation supply, enforcing selection in oxidantrich microhabitats, and supplying metabolic substrates via radiolysis. However, the current dataset does not establish a causal link. Progress will depend on integrated stratigraphic mapping of radiationproxy minerals with microbial fabrics, coupled to longduration laboratory evolution experiments that emulate Oklolike dose rates and hydrologic cycling in primitive microbes. The current study also suggests additional research is warranted. One question raised in the current study is what role, if any, did the cyclic nature of the Oklo reactor play in leading to beneficial mutations? The current study further suggests that exposing microorganisms to controlled, low level radiation can be an effective methodology for understanding the effects of such radiation on genetic change.

References

- 1.Ragheb M. (2015) Natural nuclear reactors, the Oklo phenomenon. In Chapter 6 of Nuclear, Plasma and Radiation Science .

- 2.A P Meshik, C M Hohenberg, O V Pravdivtseva. (2004) Record of cycling operation of the natural nuclear reactor in the Oklo/Okelobondo area in Gabon. Physical review letters. 93(18), 182302-10.

- 3.R T Ibekwe, C M, A J Trainer, M D Eaton. (2020) Modeling the short-term and long-term behaviour of the Oklo natural nuclear reactor phenomenon.Progress in Nuclear. Energy,118 103080.

- 4.Hidaka H. (2020) A review of in situ isotopic studies of the Oklo and Bangombé natural fission reactors using microbeam analytical techniques.Minerals. 10(12), 1060.

- 5.May D, M K Schultz. (2021) Sources and health impacts of chronic exposure to naturally occurring radioactive material of geologic origins. In Practical applications of medical geology , Cham: 403-428.

- 6.S K Jha, A C Patra, G P Verma, I S, D K Aswal. (2024) Natural radiation and environment. InHandbook on Radiation Environment, Volume 1: Sources, Applications and Policies(pp. 27-72) , Singapore: .

- 7.Talapko J, Talapko D, Katalinić D, Kotris I, Erić I et al. (2024) Health effects of ionizing radiation on the human body. , Medicina 60(4), 653.

- 9.Aubineau J, A El, Bekker A, E C Fru, Somogyi A et al. (2020) Trace element perspective into the ca. 2.1-billion-year-old shallow-marine microbial mats from the Francevillian Group. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119620 , Gabon. Chemical Geology 543, 119620.

- 10.Aubineau J, A El, E C Fru, M A Kipp, Ikouanga J N G et al. (2021) Benthic redox conditions and nutrient dynamics in the ca. 2.1 Ga Franceville sub-basin. , Precambrian Research 360, 106234.

- 11.A El, Bengtson S, D E Canfield, Riboulleau A, Bard Rollion et al. (2014) The 2.1 Ga old Francevillian biota: biogenicity, taphonomy and biodiversity. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099438 , PLoS One 9(6), 99438.

- 12.A El, M G, L A Buatois, Bengtson S, Riboulleau A et al. (2019) Organism motility in an oxygenated shallow-marine environment 2.1 billion years ago. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(9), 3431-3436.

- 13.F O Ossa, Bekker A, Hofmann A, S W Poulton, Ballouard C et al. (2021) Limited expression of the Paleoproterozoic Oklo natural nuclear reactor phenomenon in the aftermath of a widespread deoxygenation event~ 2.11–2.06 billion years ago. , Chemical Geology 578, 120315.

- 14.Ikouanga J N G, Fontaine C, Bourdelle F, Elmola Abd, Aubineau A et al. (2023) Taphonomy of early life (2.1 Ga) in the francevillian basin (Gabon): Role of organic mineral interactions. , Precambrian Research 395, 107155-10.

- 15.Soleymanifard S, Rostamyari M, Jaberi N, F B Rassouli, S I Hashemy et al. (2021) Effects of radiation dose on the stemness-related genes expression in colorectal cancer cell line. , International Journal of Radiation Research 19(3), 645-651.

- 16.Burraco P, Orizaola G. (2022) Ionizing radiation and melanism in Chornobyl tree frogs.Evolutionary. 15(9), 1469-1479.

- 17.L J Rothschild. (1999) The influence of UV radiation on protistan evolution. , Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 46(5), 548-555.

- 18.Gauthier-Lafaye F, Weber F, Ohmoto H. (1989) Natural fission reactors of Oklo. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.84.8.2286 , Economic Geology 84(8), 2286-2295.

- 19.S E Bentridi, Gall B, Nuttin A, Hidaka H. (2023) The influence of some rare earth elements as neutron absorbers on the inception of Oklo natural nuclear reactors. Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 199(18), 2269-2274.

- 20.Ershov B. (2022) Natural radioactivity and chemical evolution on the early earth: prebiotic chemistry and oxygenation.Molecules,27(23). 8584.

- 21.Piché-Choquette S, Constant P. (2019) Molecular hydrogen, a neglected key driver of soil biogeochemical processes. , Applied and Environmental Microbiology 85(6), 02418-18.

- 22.J V Henkel, H N Schulz-Vogt, Dellwig O, Pollehne F, Schott T et al. (2022) Biological manganese-dependent sulfide oxidation impacts elemental gradients in redox-stratified systems: indications from the Black Sea water column. , The ISME Journal 16(6), 1523-1533.

- 23.Jia D, Li Q, Luo T, Monfort O, Mailhot G et al. (2021) Impacts of environmental levels of hydrogen peroxide and oxyanions on the redox activity of MnO 2 particles. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts 23(9), 1351-1361.

- 24.Gauthier-Lafaye F, Gall B, S E Bentridi. (2023) The Oklo phenomenon, the discovery, first questions and first answers. Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 199(18), 2251-2257.

- 25.E, L R Nittler, D G Willingham, A P Meshik, O V Pravdivtseva. (2021) Long-term retention and chemical fractionation of fissionogenic Cs and Tc in Oklo natural nuclear reactor fuel.Applied. Geochemistry,131 105047.

- 26.Hidaka H, S E Bentridi, Gall B. (2023) Evidence of fast neutron operating. in Oklo.Radiation Protection Dosimetry,199(18) 2275-2278.

- 28.L K Fritz-. (2020) The evolution of animal cell motility. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.026 , Current Biology 30(10), 477-482.

- 29.S M Porter, L A Riedman. (2023) Frameworks for interpreting the early fossil record of eukaryotes. , Annual Review of Microbiology 77, 173-191.

- 30.Sawaki Y, Sato T, Maruyama S, Fujisaki W, Ueda H et al. (2019) Geology around natural reactors and birthplace of eukaryotes. , Chigaku Zasshi (Online) 128(4), 549-569.

- 31.M J Daly. (2023) The scientific revolution that unraveled the astonishing DNA repair capacity of the Deinococcaceae: 40 years on.Canadian. , Journal of 69(10), 369-386.

- 32.Mortazavi S M J, Rabiee S, Fallah A, Rashidfar R, Seyyedi Z et al. (2025) . Adaptive Responses in High-Radiation Environments: Insights from Chernobyl Wildlife and Ramsar Residents.Dose-Response 23(4), 15593258251385632.

- 33.A L González-Flores, Jin J, G R Osinski, C J Tsujita. (2022) . DOI: https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2021.0081 , Acritarch-like Microorganisms from the 1.9 Ga Gunflint Chert, Canada. Astrobiology 22(5), 568-578.

- 34.D G Brookins. (1990) Radionuclide behavior at the Oklo nuclear reactor. , Gabon. Waste Management 10(4), 285-296.

- 35.K A Jensen, R C Ewing. (2001) The Okélobondo natural fission reactor, southeast Gabon: Geology, mineralogy, and retardation of nuclear-reaction products. , Geological Society of America Bulletin 113(1), 32-62.

- 36.J C Nimal, T D Huynh, Tsilanizara A. (2025) Has natural radioactivity contributed to the evolution of living organisms? Validation of a dedicated calculation scheme (for isotopic concentrations and deposited energies) on Oklo's natural nuclear reactors. EPJ N-Nuclear Sciences & Technologies 11, 22.

- 37.Y V Petrov, A I Nazarov, M S Onegin, V Y Petrov, E G Sakhnovsky. (2006) Natural nuclear reactor at Oklo and variation of fundamental constants: Computation of neutronics of a fresh core. Physical Review C—Nuclear. , Physics 74(6), 064610.

- 38.Delarue F, Bernard S, Sugitani K, Robert F, Tartèse R et al. (2020) . Evidence for motility in 3.4 Gyr-old organic-walled microfossils? bioRxiv, 2020-05. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.19.103424

- 39.Geckeis H, Salbu B, Schafer T, Zavarin M. (2018) chemistry of plutonium(No. LLNL-BOOK-688957). Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) (United States). https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1606477 , Livermore, CA .