Economic Masculinity Support and Well-Being of Married Women in Luwero District, Uganda: A Cross-sectional Study

Abstract

Economic masculinity support is paramount in promoting women’s well-being through numerous ways, including enhancing access to healthcare, education, and financial freedom, hence fostering equitable distribution of household responsibilities. However, studies examining the relationship between economic masculinity support and women’s well-being have not been well established in existing research. This study evaluated the relationship between economic masculinity support and the well-being of married women in Luwero district, Uganda.

This Cross-Sectional study was conducted among 382 married women aged 18 to 50 years of age, from selected villages in Luwero district. The outcome variable, well-being, was assessed using the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM). Data were analyzed using the Pearson correlation coefficient and linear regression to ascertain the relationship between economic masculinity support and the well-being of women.

The findings show a moderate positive association between economic masculinity support and women's well-being (r = 0.55, p < 0.0001). Regression analysis indicated that economic masculinity support had a significant predictive influence (β = 0.42, p < 0.01) on women’s well-being, accounting for approximately 30% of the variance in well-being outcomes (Adjusted R² = 0.30). Linking economic masculinity supports improved access to essential resources. These results highlight the crucial role of economic support in enhancing women’s welfare, while also emphasizing the need to address socio-cultural barriers to achieve lasting empowerment.

The study underscores the significant role of economic masculinity in promoting married women’s well-being. Transforming economic masculinity into a framework of mutual support is essential for advancing gender equity and safeguarding women’s well-being globally

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Anubha Bajaj, Consultant Histopathologist, A.B. Diagnostics, Delhi, India

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2025 Priscillie Kankindi, et al

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Masculinities can either support or hinder women’s economic empowerment, particularly when married partners have joint control over household income. When husbands are supportive of their wives’ economic participation, gender role-related stress is reduced, household participation in decision-making is increased, leading to reduced risk of intimate partner violence, hence fostering the well-being of women 1, 2, 3, 4. Husbands’ positive attitude towards their wives’ economic participation is linked to improved well-being of married women, while negative attitudes impact women’s mental and physical health, employment status, and subjective health negatively. This, therefore, implies that the impact of economic masculinity support is multifaceted.

Globally, restrictive masculine norms, specifically those stressing male economic control or dominance, continue to infringe on married women’s well-being in reflective ways3. In local communities where men are expected to provide solely, women are often denied the opportunity to engage in economically generating activities. This leads to limited autonomy among the women and financial dependency. In some cases, where women have surpassed their male counterparts by earning more, this has resulted in punitive consequences 3 and separation or divorce 4.

In Latin America, such dynamics have been reported to provoke both physical and emotional violence as the men attempt to reassert dominance, hence escalating gender-based violence 4. Literature further posits that men who strongly kowtow to controlling masculine ideas are more likely to commit intimate partner violence, especially in economically strained homes 4. For instance, in societies where men stay at home in a culture where dominant concepts of masculinity cast men as breadwinners, women face social challenges as a result of gender social stress mechanisms, as social pressures reinforce gender culture and norms, inflicting stress on gender-non-conforming partners 4.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the impact extends beyond physical safety to women’s mental and physical well-being 5. Married women often carry the double burden of paid and unpaid domestic labor, with little support from partners who resist evolving gender roles. This inequality fosters chronic stress, reduces decision-making power, and diminishes access to health services, especially in contexts where men control the household finances 6, 7, 8, 9. Moreover, men’s resistance to shifting norms can take subtle but damaging forms such as emotional withdrawal, refusal to contribute to childcare, or abandoning the relationship altogether.

In Seria leone, masculinity support has been linked to uptake of health services challenges, particularly in rural areas where primary health care infrastructure is weak 10, as women require financial support from their partners to facilitate transport cost to the health facilities, which in turn affects household financial security as financial decisions about household health is made 11.

In Africa, countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Kenya have reported a negative impact of economic masculinity among married women rooted in patriarchal norms, which limits their access to health care, decision making, financial abuse, domestic violence, denied employment opportunities, and unequal distribution of household responsibilities 12, 13, 14. On the other hand, women’s income generation, whether through employment or entrepreneurship, can lead to increased financial security for themselves and their families, allowing them to afford necessities, save money, and invest in their children’s activities, it can exacerbate gender role stress and potentially lead to mental health challenges 15, 4.

In Uganda, masculinity is deeply intertwined with the role of the man as the primary provider for the household. The UN Women 16 found that when women lack control over financial resources, economic provision can reinforce traditional dependency rather than promote autonomy. Ahikire and Mwiine argue that in Uganda, although financial support from men improves immediate material conditions, it rarely shifts underlying power dynamics unless coupled with broader cultural change 17.

A study conducted in Rakai district found that masculine norms of respectability impact the well-being of women, as men place masculinity in a position of power and tend to control everything in the family, hence limiting the economic growth of women 18.

In Luwero District, traditional cultural expectations strongly influence the economic interactions between men and women. Economic masculinity support, which refers to the provision of financial resources, entrepreneurial support, and access to economic opportunities by men, plays a significant role in shaping the lives of women 19.

Uganda has embraced the Global Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals, integrating them into national strategies. The country’s Vision 2040 identifies gender equality as a fundamental driver of socio-economic progress, while the National Development Plan (NDP) II 20emphasizes empowering women and advancing gender equity as essential pathways to achieving inclusive growth and fostering social development.

Literature suggests that while economic masculinity support is crucial for enhancing women’s well-being, it must be accompanied by efforts that promote women’s financial autonomy and challenge traditional gender expectations. However, emerging efforts to reshape these norms offer hopeful pathways forward. Gender-transformative programs around the world are engaging men to rethink masculinity as rooted in partnership rather than control 3. Initiatives that promote shared household responsibilities and inclusive decision-making have shown promising results: improved relationship quality, enhanced women’s agency, and better health outcomes for entire families. Ultimately, transforming economic masculinity into a framework of mutual support is essential for advancing gender equity and safeguarding women’s well-being globally 3.

Although Uganda has made strides toward gender equality through legal frameworks such as the 1995 Constitution and the Gender Policy 21, in rural areas like Luwero, women's economic empowerment remains limited. This study seeks to explore whether economic masculinity support genuinely improves women’s well-being and, if so, whether it leads to their sustainable empowerment or reinforces dependency within the traditional gender hierarchy.

Methodology

Study design, setting, and population

The study adopted a cross-sectional design to achieve a comprehensive understanding of economic masculinity support and its effect on women's well-being. Quantitative data were collected through structured researcher-administered questionnaires among 382 married women selected from Bamunanika, Kamira, Zirobwe, and Kalagala sub-counties. Key indicators included household income, food security, access to healthcare services, education enrollment for children, and quality of housing.

The study population consisted of married women aged 18 to 50 years residing in the selected villages (Bamunanika, Kamira, Zirobwe, and Kalagala sub-counties) in Luwero district. Participants were recruited using a simple random sampling technique to ensure equal opportunity to participate in the study. The study excluded married couples who have been married for less than one year, as they may not provide a true picture of the variables of interest in the study.

Data Collection Process and Quality Control Measures

The data were collected using a pilot-tested researcher-administered questionnaire between July 2024 and August 2024. Informed consent to participate in research was sought before participants were enrolled in the study, the questions were translated into Luganda – the local language spoken in central Uganda and the data enumerators were trained researchers who had knowledge of and understood Luganda. The data enumerators were knowledgeable and had experience in conducting health-related surveys among older persons. To ensure data accuracy, the study team held weekly meetings to compare notes, address any issues arising during data collection, and prepare preliminary findings. During data collection, relevant information not captured in the questionnaire was recorded as field notes and recorded in notebooks.

Study variable and measurements

The key variables in the study were the independent variables (economic masculinity support), and the dependent variable (well-being). The outcome variable, well-being, was assessed using the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM).

Data analysis

Data analysis was done using Stata version 18. The authors hypothesized that there is a relationship between economic masculinity support and the well-being of married women in Luwero district. This hypothesis was informed by the fact that marriage offers financial protection to women, which may influence their economic well-being.

The authors employed frequencies and percentages to analyze demographic data, and Data were analyzed using the Pearson correlation coefficient and linear regression to ascertain the relationship between economic masculinity support and the well-being of women. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was 0.8 with an internal content validity of 0.75, indicating good internal consistency. Using descriptive analysis, the authors were able to summarize data in the form of means and frequencies to explain the demographic characteristics of the study respondents. STATA version 18 was used to analyse the data to confirm variables that influence well-being. Only variables that had a p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant in this study.

Quality Control Measures

To ensure high-quality data collection, data enumerators underwent training tailored to the study’s objectives. These enumerators possessed prior experience in quantitative data collection, particularly with vulnerable populations such as older adults. The research tools were pilot tested to assess their reliability and validity. Data entry and cleaning were conducted daily to minimize recall bias and promote completeness and accuracy. Weekly meetings provided a platform for reflection, troubleshooting emerging challenges, and supporting report writing efforts.

Ethical Issues

The study obtained ethical approval from the Clarke International University Research Ethics Committee (CIUREC), along with clearance from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST). In addition, administrative permission was granted by local leaders in selected villages of Luwero district. Before participant enrollment, written informed consent was obtained. To enhance understanding of the study’s objectives and procedures, both the data collection tools and consent forms were translated into Luganda, the predominant local language. Participants were assured of their voluntary involvement and the confidentiality of their information. The informed consent form also included a clause permitting the future publication of study findings.

Results

The initial desired sample size of the study was 396, but due to non-response issues resulting from some married women's fear of participating in the study, the sample size was reduced to 382, giving a response rate of 96.5%.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Respondents

The respondents in this study were fairly distributed across the four sub-counties, with Kalagala contributing the highest proportion (31.7%) and Kamira the lowest (17.5%). The sample predominantly consisted of younger individuals, with 55.2% aged between 18–34 years and 36.1% aged between 35–50 years, indicating a youthful population likely to have evolving economic needs and social expectations. In terms of occupation, businesswomen (24.9%) and farmers (24.6%) were the most common, reflecting a community heavily reliant on self-employment and agriculture. As shown in Table 1, formal employment was relatively rare, with only 6.5% engaged in salaried jobs and 1.8% in casual labor. Marital status data revealed that 40.1% of respondents were cohabiting, 31.4% were in monogamous marriages, and 28.5% were in polygamous unions, illustrating the continued influence of traditional and informal marital arrangements.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Respondents| Variable | Frequency (n=382) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-County | ||

| Bamunanika | 90 | 23.56 |

| Kalagala | 121 | 31.68 |

| Kamira | 67 | 17.54 |

| Zirobwe | 104 | 27.23 |

| Age group | ||

| 18-34 | 211 | 55.24 |

| 35-50 | 138 | 36.13 |

| 51 and above | 33 | 8.64 |

| Occupation | ||

| Business person | 95 | 24.87 |

| Causal labourer | 7 | 1.83 |

| Civil Servant/Salaried job | 25 | 6.54 |

| Farmer | 94 | 24.61 |

| None | 81 | 21.20 |

| House Wife | 80 | 20.94 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Cohabiting | 153 | 40.05 |

| Married Monogamous | 120 | 31.41 |

| Married Polygamous | 109 | 28.53 |

| Income level | ||

| 100,000- 200,000/= | 62 | 16.23 |

| Above 200,000 | 42 | 10.99 |

| Less than 100,000 | 141 | 36.91 |

| None | 137 | 35.86 |

| Education level | ||

| None | 100 | 26.18 |

| Primary | 117 | 30.63 |

| Secondary | 125 | 32.72 |

| Tertiary | 40 | 10.47 |

Economically, the community faces significant vulnerabilities, with 36.9% of respondents earning less than 100,000 UGX per month and 35.9% reporting no income at all. Only a minority earned above 100,000 UGX, pointing to widespread financial insecurity. Educational attainment was similarly low; while 32.7% had completed secondary education and 30.6% had completed primary school, 26.2% reported having no formal education, and only 10.5% had tertiary qualifications. These findings suggest that the population is characterized by youthfulness, economic dependency, limited access to formal employment, and restricted educational opportunities. Understanding this demographic profile is critical for interpreting the results of the study, as these socio-economic characteristics shape women’s experiences with economic masculinity support and their overall well-being

Well-being of women

The findings reveal critical concerns related to women’s wellbeing in Luwero. The top three areas of concern, based on the highest Likert means, are food insecurity (Mean = 3.474) with 64.66% agreeing or strongly agreeing that they often worry about their food running out before they can afford to buy more; reliance on herbal medicine (Mean = 3.217) hard a notable trend, with 56.54% agreeing or strongly agreeing that they often seek medical care from herbalists rather than formal healthcare facilities; and unemployment(Mean = 3.212) a major concern, with 56.54% of respondents identifying as housewives and considering themselves unemployed. Additionally, 56.28% agreed or strongly agreed that they do not have a job to raise income for their families (Mean = 3.160). This points to a widespread lack of formal employment opportunities for women in the area.

Table 2. Respondents’ perception on wellbeing| Wellbeing of Women | SD | D | NS | A | SA | Mean | Standard deviation | Sample (n) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My children dropped out of school due to lack of school fees and scholastic materials. | 33.77 | 35.34 | 4.45 | 20.68 | 5.76 | 2.293 | 1.283 | 382 | Low |

| My children cover long distances of over 5kms to school. | 34.82 | 28.53 | 3.66 | 26.96 | 6.02 | 2.408 | 1.358 | 382 | Low |

| My children do not study in high valued standard school. | 29.84 | 23.82 | 4.71 | 36.13 | 5.5 | 2.636 | 1.373 | 382 | Moderate |

| I don’t know how to read and write | 25.92 | 23.3 | 7.33 | 32.2 | 11.26 | 2.796 | 1.416 | 382 | Moderate |

| I lack a personal house in which to stay with my family members. | 21.99 | 30.37 | 3.93 | 21.73 | 21.99 | 2.914 | 1.51 | 382 | Moderate |

| My house lacks water for domestic use | 16.23 | 39.79 | 3.14 | 28.53 | 12.3 | 2.809 | 1.339 | 382 | Moderate |

| My does not have enough electricity for domestic use | 17.54 | 32.98 | 3.93 | 28.53 | 17.02 | 2.945 | 1.414 | 382 | Moderate |

| My house lacks a latrine (toilet facilities) | 37.43 | 48.17 | 2.36 | 7.07 | 4.97 | 1.94 | 1.062 | 382 | Very Low |

| My house is not permanent and leaks when it rains | 32.2 | 42.67 | 10.21 | 9.42 | 5.5 | 2.134 | 1.132 | 382 | Low |

| I cannot afford health services for myself or for my children | 21.47 | 29.58 | 5.76 | 34.03 | 9.16 | 2.798 | 1.351 | 382 | Moderate |

| We often obtain medical care from herbalists | 10.99 | 26.7 | 5.76 | 42.67 | 13.87 | 3.217 | 1.283 | 382 | Moderate |

| I walk more than 5kms to the nearest health Centre/hospital. | 20.94 | 27.49 | 4.19 | 37.43 | 9.95 | 2.88 | 1.369 | 382 | Moderate |

| I spend more time waiting for health services | 15.45 | 23.56 | 3.14 | 49.74 | 8.12 | 3.115 | 1.291 | 382 | Moderate |

| The health workers are not experienced which puts my life at a risk. | 28.53 | 29.84 | 17.54 | 19.9 | 4.19 | 2.414 | 1.211 | 382 | Low |

| My family is unable to get three meals per day | 25.39 | 26.18 | 4.45 | 37.96 | 6.02 | 2.73 | 1.353 | 382 | Moderate |

| I do not grow my own food | 18.06 | 24.61 | 3.93 | 39.27 | 14.14 | 3.068 | 1.388 | 382 | Moderate |

| I am sometimes worried that my food would run out before I get money to buy more. | 11.52 | 18.06 | 5.76 | 40.84 | 23.82 | 3.474 | 1.335 | 382 | Moderate |

| I lack the ability to have a balanced diet composed of Vitamins, Carbohydrates and Proteins among others. | 11.78 | 32.2 | 5.24 | 40.58 | 10.21 | 3.052 | 1.268 | 382 | Moderate |

| I am a peasant farmer (grow crops & rear animals). | 26.7 | 17.02 | 6.28 | 36.39 | 13.61 | 2.932 | 1.465 | 382 | Moderate |

| I don’t have a job to raise income for my family | 16.49 | 23.3 | 3.93 | 40.31 | 15.97 | 3.16 | 1.383 | 382 | Moderate |

| I am a housewife and therefore unemployed. | 14.66 | 23.82 | 4.97 | 38.74 | 17.8 | 3.212 | 1.373 | 382 | Moderate |

| Overall | 2.806 | 0.764 | 382 | Moderate |

The relationship between economic masculinity support and the well-being of married women

Economic masculinity support reflects the extent to which husbands contribute to their families' financial stability and empower their wives in economic decisions. In many households, traditional gender norms in Luwero reinforce male dominance in financial matters, limiting women's control over resources and economic opportunities. Many women face financial neglect, lack decision-making power over land and property, and experience restrictions on employment and income-generating activities. These dynamics contribute to economic dependence, making it difficult for women to support their families, access financial opportunities, and achieve financial independence.

Table 3. Respondents' perceptions of economic masculinity support| Economic Masculinity Support | SD | D | NS | A | SA | Mean | Standard deviation | Sample (n) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My husband does not support me in the education of our children. | 34.03 | 31.41 | 7.59 | 15.45 | 11.52 | 2.390 | 1.387 | 382 | Low |

| My husband does not want to construct a house for our family, nor pay rent for our accommodation. | 27.49 | 37.7 | 8.38 | 15.97 | 10.47 | 2.442 | 1.322 | 382 | Low |

| I cannot dig the land without permission of my husband. | 23.04 | 32.2 | 8.12 | 16.75 | 19.9 | 2.783 | 1.471 | 382 | Moderate |

| I cannot sell an animal without permission of my husband. | 16.49 | 23.82 | 8.9 | 30.37 | 20.42 | 3.144 | 1.415 | 382 | Moderate |

| I lack access to land and other resources for use at home | 18.06 | 30.37 | 8.38 | 22.77 | 20.42 | 2.971 | 1.441 | 382 | Moderate |

| My husband does not seek my agreement before buying anything big for example, land, vehicle, motorbike, among others. | 23.56 | 28.01 | 7.85 | 24.08 | 16.49 | 2.819 | 1.448 | 382 | Moderate |

| My husband does not help me get a loan for my income-generating project. | 17.02 | 32.46 | 10.21 | 21.47 | 18.85 | 2.927 | 1.405 | 382 | Moderate |

| My husband discourages me in joining SACCO and VSLA groups. | 17.02 | 37.7 | 9.16 | 17.8 | 18.32 | 2.827 | 1.394 | 382 | Moderate |

| My husband does not provide money for transport when I am to visit the health facility. | 18.59 | 44.5 | 7.59 | 17.28 | 12.04 | 2.597 | 1.298 | 382 | Moderate |

| My husband does not buy clothes and shoes for me. | 21.47 | 44.24 | 7.07 | 17.54 | 9.69 | 2.497 | 1.271 | 382 | Low |

| My husband does not provide food at home. | 30.37 | 42.15 | 7.85 | 11.52 | 8.12 | 2.249 | 1.231 | 382 | Low |

| My husband stopped me from being employed. | 28.53 | 32.98 | 8.9 | 20.94 | 8.64 | 2.482 | 1.327 | 382 | Low |

| My husband has not supported me in starting a business. | 25.13 | 36.91 | 8.64 | 18.06 | 11.26 | 2.534 | 1.339 | 382 | Low |

| My husband does not have a job to raise money to support our family. | 27.49 | 39.53 | 8.12 | 15.71 | 9.16 | 2.395 | 1.287 | 382 | Low |

| Overall | 2.647 | 1.004 | 382 | Moderate |

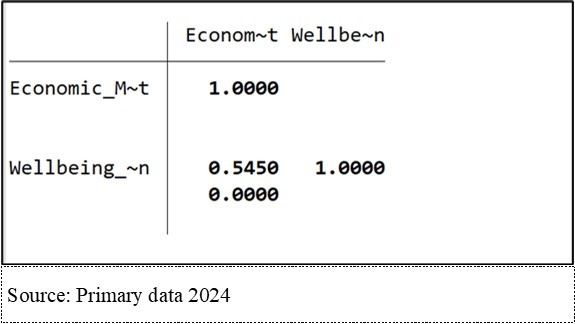

Correlation between economic masculinity support and the well-being of women

A correlation between 0.00 and 0.19 is considered very weak, indicating little to no relationship between variables. The range of 0.20 to 0.39 represents a weak correlation, suggesting a small but noticeable connection. A correlation between 0.40 and 0.59 is classified as moderate, showing a meaningful but not definitive relationship. When the coefficient falls between 0.60 and 0.79, it is considered strong, indicating a significant association between the variables. A correlation ranging from 0.80 to 1.00 is classified as very strong, meaning the variables have a highly consistent and predictable relationship.

The correlation analysis between economic masculinity support and the well-being of women shows a moderate positive relationship, with a correlation coefficient of 0.55. This indicates that as economic masculinity support increases, the well-being of women also tends to improve. The p-value of 0.0000 confirms that this correlation is statistically significant, meaning the observed relationship is highly unlikely to have occurred by chance.

The moderate positive correlation suggests that increases in economic masculinity support are associated with improvements in various dimensions of women’s wellbeing, including physical health, mental health, and overall quality of life. The statistically significant p-value of 0.0000 further reinforces the reliability of this relationship, indicating that the findings are not due to random chance.

Table 4.Correlations between economic masculinity support and the well-being of women

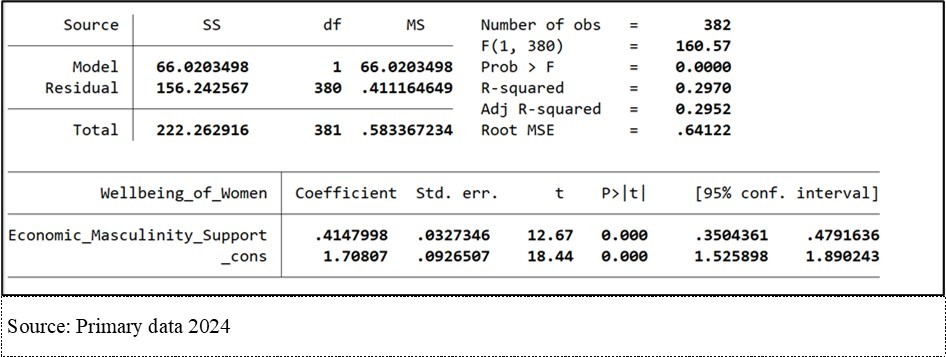

Regression analysis results for the influence of economic masculinity support and the well-being of women

Regression analysis further confirmed the significance of economic masculinity support in predicting women's well-being. The regression coefficient for economic masculinity support was 0.42, meaning that each unit increase in economic masculinity support leads to a 0.42-unit improvement in women's well-being. This relationship was highly statistically significant at the 1% level (p < 0.01), reinforcing the strength of the link.

The model’s adjusted R-squared value was rounded off to 0.30, indicating that approximately 30% of the variability in women’s well-being can be explained by economic masculinity support. While this is substantial, it also suggests that other factors account for the remaining 70% of well-being variability, highlighting the complexity of women's lives and the influence of multiple determinants beyond economic support.

Table 5.Regression analysis for the influence of economic masculinity support and the well-being of women

Model findings

Findings of the linear regression model revealed a strong positive relationship between economic masculinity support and women's well-being. The linear regression analysis demonstrated that economic support significantly enhanced women’s access to key resources (β = 0.42, p < 0.000). Women who received consistent financial support from their spouses reported greater food security, better access to healthcare services, improved school enrollment for their children, and better housing conditions.

Discussion

The study’s findings highlight the significance of economic masculinity support in enhancing women’s overall well-being, indicating that an increase in economic masculinity increases women's well-being. The findings emphasize the importance of financial resources in improving women's well-being. These findings align with existing literature, which posits that economic stability and support influence access to healthcare, education, and other essential services 11, 15, 4.

Findings also revealed a moderate relationship between economic support and women's access to basic needs such as food, healthcare, education, and housing. However, cultural norms restricting women’s control over financial resources were identified as a limiting factor to sustainable empowerment. The study recommends promoting financial literacy, joint financial decision-making, and community sensitization to transform cultural attitudes toward gender relations. In a similar vein, 22 investigated the effects of targeted financial interventions on women's health and well-being in urban settings. Their findings revealed that women who received economic support through financial literacy programs and employment initiatives reported higher levels of life satisfaction and reduced anxiety related to financial instability. This aligns with the current study's assertion that economic support alleviates stress and fosters a sense of agency among women, highlighting the multifaceted benefits of such interventions.

Additionally, a 2021 study provides insights into the long-term effects of economic empowerment on women’s health 23. Their longitudinal research indicated that women who experienced sustained economic support over time exhibited better health outcomes and a more positive outlook on life. This supports the current findings that suggest economic support enhances not only immediate well-being but also contributes to a sustained improvement in quality of life

From a researcher’s perspective, these findings highlight the vital intersection between economic masculinity support and empowerment. Economic masculinity support does not merely provide financial resources; it also fosters a sense of agency and self-efficacy among women. As women experience increased financial autonomy, they are more likely to make decisions that enhance their well-being, from health choices to educational pursuits for their children. Additionally, policymakers should prioritize economic empowerment initiatives, including access to financial resources and educational opportunities, as they are instrumental in enhancing women's well-being. As stated by several scholars 11, 15, 4, the intersection of economic support and emotional well-being is crucial in creating sustainable change for women. By creating supportive environments that prioritize both emotional and economic well-being, we can foster healthier communities and ultimately promote greater gender equity.

The Role of Entrepreneurial Support

Beyond basic financial provision, entrepreneurial support emerged as a critical factor in enhancing women's autonomy. Women who received capital support, mentorship, or encouragement to start income-generating activities displayed greater financial independence and confidence.

Persistent Challenges and Limitations

Despite the positive impacts, the study identified several persistent challenges. In many cases, while women had access to financial resources, ultimate control remained with their male partners. Economic support was often conditional on women fulfilling traditional roles such as caregiving and domestic service.

Moreover, disputes within households sometimes resulted in the withdrawal of financial support, thereby reasserting male dominance. Such dependency made women vulnerable to economic insecurity and limited their ability to make autonomous decisions. These findings highlight the limitations of economic support that is not paired with genuine empowerment and autonomy.

The current study had several strengths and limitations. The first key strength is that it is among the few studies globally to examine the influence of economic masculinity support on married women's well-being. The study was conducted in rural areas, depicting a clear picture of economic masculinity support among women in rural-poor villages. We obtained a sufficient sample size, which enabled the team to determine associations. In terms of limitations, the study employed a cross-sectional design, which is limited in terms of examining causal effects. The study targeted married women from selected villages in Luwero district, which may not fully capture the entire district status. More research should be conducted with a focus on the entire married women in Luwero district.

Gaps Between Policy and Practice

Although Uganda's policies advocate for women’s economic empowerment, practical implementation at the local level is weak. Many women in Luwero District reported difficulties in accessing independent credit, land ownership, and formal employment opportunities. As a result, the benefits of economic masculinity support were often short-term and fragile, dependent largely on the stability of marital relationships rather than institutional guarantees of rights.

Conclusion

The findings demonstrated that economic masculinity support significantly improves the immediate well-being of women in Luwero District by enhancing access to food, healthcare, education, and housing. However, true empowerment requires more than financial provision; it demands that women have the autonomy to control and allocate financial resources. Without addressing the cultural and structural barriers that restrict women’s independence, economic support risks reinforcing traditional dependencies rather than creating pathways to sustainable empowerment.

Recommendations

The government of Uganda, through the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development (MoGLSD), should promote financial literacy programs widely across the district to equip women with the knowledge and confidence to manage resources independently. Initiatives that encourage joint financial planning between spouses should be developed, fostering a spirit of partnership rather than control. Entrepreneurial programs targeting women should be expanded, providing access to start-up capital, training, and mentorship. Community sensitization campaigns should challenge restrictive gender norms, promoting a vision of masculinity that supports equality and shared responsibility. Enforcement of gender equality policies must be strengthened, ensuring that women have legal access to credit, land, and employment opportunities independent of male control. Only through a combined focus on financial support, empowerment, and cultural change can economic masculinity support truly enhance the well-being and prospects of women in Luwero District.

These results imply that interventions aimed at increasing economic masculinity support for women, such as financial literacy programs, access to credit, and employment initiatives, could have far-reaching effects on their well-being. By addressing economic disparities and promoting financial independence, policymakers and organizations can facilitate improvements not only in women’s quality of life but also in their families and communities.

Authors contribution

All authors contributed to the study. PK conceptualized the study and participated in writing the manuscript; FA participated in manuscript writing and editing; MM and CE supervised the entire research process as the study supervisors.

Funding

This study was self-sponsored, so no funding was received.

Data availability

Data is available on request

Abbreviations

Labour and Social Development

SACCO: Saving and Credit Cooperative UND: National Development Plan UNCST: Uganda National Council for Science and TechnologyReferences

- 2.L. (2012) Determinants of partner violence in low and middle-income countries: exploring variation in individual and population-level risk (Doctoral dissertation. , London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine)

- 3.OECD. (2021) Enough? Measuring Masculine Norms to Promote Women’s Empowerment, Social Institutions and Gender Index.

- 4.A M Buller, Hidrobo M, Peterman A, Heise L. (2016) The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach?: a mixed methods study on causal mechanisms through which cash and in-kind food transfers decreased intimate partner violence.BMC public health,16. 1-13.

- 5.Gonalons-Pons P, Gangl M. (2021) Marriage and Masculinity: Male-Breadwinner Culture, Unemployment, and Separation Risk in 29 Countries.American sociological review,86(3). 465-502.

- 6.Seymour G, Peterman A. (2018) Context and measurement: An analysis of the relationship between intrahousehold decision making and autonomy.World. Development,111 97-112.

- 7.Zegenhagen S, Ranganathan M, A M Buller. (2019) Household decision-making and its association with intimate partner violence: Examining differences in men's and women's perceptions in Uganda. SSM-population health,8. 100442.

- 8.Hughes C, Bolis M, Fries R, Finigan S. (2015) Women's economic inequality and domestic violence: exploring the links and empowering women. , Gender & Development 23(2), 279-297.

- 9.Hu Y, Li J, Ye M, Wang H. (2021) The relationship between couples’ gender-role attitudes congruence and wives’ family interference with work.Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 49-59.

- 10.Gwak H, Choi E. (2015) Influence factors of labor force participation for married women: Focusing on the gender unequal structure in household and labor market.Womens. Study,88 429-456.

- 11.Sharkey P, Torrats-Espinosa G, Takyar D. (2017) Community and the crime decline: The causal effect of local nonprofits on violent crime. , American Sociological 82(6), 1214-1240.

- 12.Treacy L, H A Bolkan, Sagbakken M. (2018) Distance, accessibility and costs. decision-making during childbirth in rural Sierra Leone: a qualitative study.PLoS One,13(2).

- 14.Kalonda Omba, C J. (2011) Socioeconomic impact of armed conflict on the health of women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.Medecine tropicale: revue du corps de sante. 71(2), 192-196.

- 15.Peterman A, Schwab B, Roy S, Hidrobo M, D O Gilligan. (2015) Measuring women's decision making: indicator choice and survey design experiments from cash and food transfer evaluations in Ecuador. , Uganda, and Yemen

- 16. (2022) UN Women.Progress on the sustainable development goals: Gender snapshot.New. , York, NY: UN Women

- 17.Ahikire J, Mwiine A. (2015) equality in Uganda: A status report.Kampala: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- 18.Park E, S J Wolfe, Nalugoda F, Stark L, Nakyanjo N et al. (2022) Examining Masculinities to Inform Gender-Transformative Violence Prevention Programs: Qualitative Findings From Rakai, Uganda.Global health. , science and 10(1), 2100137-10.

- 19.Nabasirye M, E M Kyomuhangi-Manyindo, Namuddu R. (2024) . , THE INFLUENCE OF CULTURAL NORMS ON FINANCIAL EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN IN UGANDA’S MICRO AND SMALL ENTERPRISES.Research Journal of Business and 11(1), 51-59.

- 20.Kasule Nabwowe, Mncwabe A, N. (2019) Social and Economic Rights in Uganda: Has the National Development Plan II (2015/16-2019/20) lived up to its Expectations?.

- 21.Nkurunungi C. (2019) A critical review on how women emancipation has been achieved since the 1995 constitution of the republic of Uganda.