Abstract

The study was conducted in four selected hospitals in the Southern part of India with an aim to determine the support needs of women in early labour as perceived by women. A descriptive design was used to determine the support needs of women in early labour. Following ethical approval, sixty women between 29-40 weeks of gestation with singleton pregnancy were interviewed in early labour, using a validated Labour Support Need Assessment Tool to gather data on background information and perception of women related to need and support needs (physical, emotional and informational support). Results indicated that women perceived all types of support such as physical, emotional and informational as significant factors in their care during labour, regardless of their parity and gestation. The major findings of the study suggested that there was a slightly higher need for support among women for informational (90.33%) and emotional support (88.78%) compared to physical support (80.19%). For primigravid women, and multiparous women who were experiencing labour for the first time (previous birth by caesarean section), the ‘need for support’ was greater than for women who had previous experience of labour. Early labour is the time when most women use their own coping skills and seek support. Determining the quantity and quality of support women need at this phase of labour can help care providers to provide the best comprehensive care to women in early labour. The findings of the study provide a guide on what women feel is helpful in early labour.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Adewale Ashimi, Department of obstetrics and gynecology Federal medical centre, Birninkudu, Jigawa state, Nigeria.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2016 Sunita Panda, et al

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Giving birth is the most special and memorable moment in a woman's life. Women always remember their childbirth experience, and often find it very positive and enjoyable. However, some women find childbirth frightening and are quite anxious about it. Understanding women’s needs during this crucial period is one of the first steps to help and support women to achieve the most satisfying experience.

Different aspects of labour support, either to improve birth outcomes or to make labour a more satisfying experience for women and their families have been studied in the world literature. Smith’s work on developing a labour satisfaction questionnaire has found high correlation between ‘professional support in labour’ and maternal satisfaction.1 Integration of Reva Rubin's framework and social support theory has formed a foundation for intrapartum nursing with main focus on psychological milieu, support in labour to improve birth outcomes, enhancement of self-value and strengthening the transition to motherhood. Social support, on the other hand, mainly focuses on strengthening interpersonal transaction through emotional, physical and informational support. 2

Women's views on supportive behaviours of nurses have been categorised as emotional, informational and tangible support and findings have suggested that, regardless of the pain management used, nurses supporting childbearing women must not only be competent but also use a high degree of interpersonal skills in providing nursing care.3 Similar findings from women’s perspectives suggest professional competency and monitoring of women’s condition during labour as other helpful behaviours.4 Women following normal childbirth have described such helpful coping measures as performing roles of emotional support providers, comforters, information/advice providers, professional technical skill providers and advocates. Unhelpful nursing actions were also described, such as failure to provide emotional support, comfort, information and advice, and technical duties.5 Nursing support behaviours by care providers have been perceived as helpful by women experiencing labour for the first time and indicative of their expectations of their care providers in relation to coping with pain, nursing support, support from partner and medical intervention.6

On the other hand, studies of care providers' perspectives to describe specific supportive measures that best describe labour support have primarily included psychosocial support such as reassurance, and physical support such as providing comfort through simple measures like position change.7, 8 Overall, literature on perspectives of women in labour and health care providers clearly indicate that there is an expectation from women in labour related to the need for physical, emotional and informational support. Thus, this study was conducted in order to determine the physical, emotional and informational support needs of Indian women in early labour.

Methods

Design

A descriptive study design using a developed and validated quantitative data collection tool was used. Maternity service in India is mostly part of primary health care services and this study was conducted in the maternity wards of four selected hospitals (three tertiary care level hospitals and one specialised maternity hospital) of Karnataka, India.

Purposive sampling technique was used to select the participants of the study and these included women of 20-40 years of age with singleton pregnancy between 29-40 weeks of gestation attending the four study sites in early labour.

Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection and data were collected through interviews with 60 women in the latent phase of first stage of labour using a Labour Support Need Assessment Tool (LSNAT). The LSNAT was developed from relevant literature and it had two sections. Section one included background information of women and section two included 40 questions related to women's perception of needs and needs for physical, emotional and informational support. The draft tool was assessed for content validity by 9 experts in the field of maternity nursing, and modifications were made as suggested. Reliability was tested by using Crohnbach’s alpha, with a reliability coefficient of r=0.821. A pilot study was conducted with 6 women in the latent phase of first stage of labour to test the acceptability and utility of the final tool (Figure 1).

Figure 1.Examples of questions in LSNAT (Labour Support Need Assessment Tool)

Data analysis was done manually. Data related to sample characteristics were described using frequency and percentage distribution, and data related to women's perception of needs and need for physical, emotional and informational support were described using mean, mean percentage distribution of scores and standard deviation.

For each of the needs, and need for support, the mean score and standard deviation was obtained. The mean score was obtained by dividing obtained maximum score by the total number of women (n=60). The mean percentage distribution of score was obtained by dividing mean score by the maximum assigned score for each area multiplied by 100.

Results

Results are presented under sample characteristics, labour support needs (physical, emotional and informational) and support needs among primigravid and multigravid women.

Of the 60 women who participated in the study, 33 (55%) were of 20-25 years of age. The majority (44, 73.33%) were primigravida and the remainder were multigravida of which 10 (16.67%) women had past experience of labour. Of the 60 women, 35 (58.33%) were of term gestation, 23 women (38.34%) were post term and only two women (3.33%) were of pre term gestation (between 29 to 37 weeks of gestation). Data related to labour support included needs and need for support of women in labour in the three aspects, physical, emotional and informational support needs. The findings are presented in terms of scores described as low (0-19), moderate (20-39) and high (40-60) (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean percentage distribution and standard deviation (SD) of scores under physical, emotional and informational support needs (n=60)| Support Needs | Maximum Score | Needs ( n = 60) | Need for support ( n = 60) | ||||

| Mean score | Mean % distribution of score | SD | Mean score | Mean % distribution of score | SD | ||

| Physical | 27 | 21.33 | 79.00 | 1.87 | 21.65 | 80.19 | 2.99 |

| Emotional | 18 | 15.93 | 88.50 | 1.11 | 15.98 | 88.78 | 1.44 |

| Informational | 15 | 13.41 | 89.40 | 0.53 | 13.55 | 90.33 | 0.59 |

The physical support needs of women are presented in relation to positioning, ambulation, hydration, elimination and hygiene during labour. The mean percentage distribution of scores under physical support needs were highest in needs (100%) as well as need for support (100%) for ‘maintenance of hygiene’ and were lowest in needs (49.33%) in ‘positioning’ and need for support (52.33%) in ‘maintenance of hydration during labour’ (Table 2). The emotional support needs were described in relation to reassurance, visual/tactile/mental stimuli, distraction and encouragement during labour. The mean percentage distribution of scores were highest for needs (100%) as well as need for support (100%) for ‘reassurance’, ‘distraction’ and ‘encouragement’ and lowest in needs (77.11%) and need for support (77.55%) for ‘attention focussing’ during labour (Table 3). The informational support needs were described in relation to ‘information sharing’ and ‘advice’ during labour. The mean percentage distribution of scores under informational support category were highest in needs (100%) as well as need for support (100%) related to ‘information sharing’ and lowest in needs (47.33%) and need for support (48.33%) for ‘advice’ during labour (Table 4).

Table 2. Mean, mean percentage distribution and standard deviation (SD) of scores under physical support needs. (n=60)| Areas | Maximum Score | Needs ( n = 60) | Need for support ( n = 60) | ||||

| Mean score | Mean % distribution of score | SD | Mean score | Mean % distribution of score | SD | ||

| Positioning | 3 | 1.48 | 49.33 | 0.50 | 1.63 | 54.33 | 0.80 |

| Ambulation | 3 | 1.52 | 50.67 | 0.50 | 1.67 | 55.67 | 0.80 |

| Hydration | 3 | 1.50 | 50.00 | 0.50 | 1.56 | 52.33 | 0.74 |

| Elimination | 6 | 4.83 | 80.56 | 0.37 | 2.40 | 80.00 | 0.65 |

| Hygiene | 12 | 12.00 | 100 | a | 3.00 | 100 | a |

| Areas | Maximum Score | Needs ( n = 60) | Need for support ( n = 60) | ||||

| Mean score | Mean %distribution of score | SD | Mean score | Mean % distribution of score | SD | ||

| Reassurance | 3 | 3 | 100 | a | 3 | 100 | A |

| Attention focussing | 9 | 6.94 | 77.11 | 1.12 | 6.98 | 77.55 | 1.44 |

| Distraction | 3 | 3 | 100 | a | 3 | 100 | A |

| Encouragement | 3 | 3 | 100 | a | 3 | 100 | A |

| Areas | Maximum Score | Needs (n = 60) | Need for support (n = 60) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean score | Mean % distribution of score | SD | Mean score | Mean % distribution of score | SD | ||

| Information sharing | 12 | 12 | 100 | a | 12 | 100 | a |

| Advice | 3 | 1.42 | 47.33 | 0.53 | 1.45 | 48.33 | 0.59 |

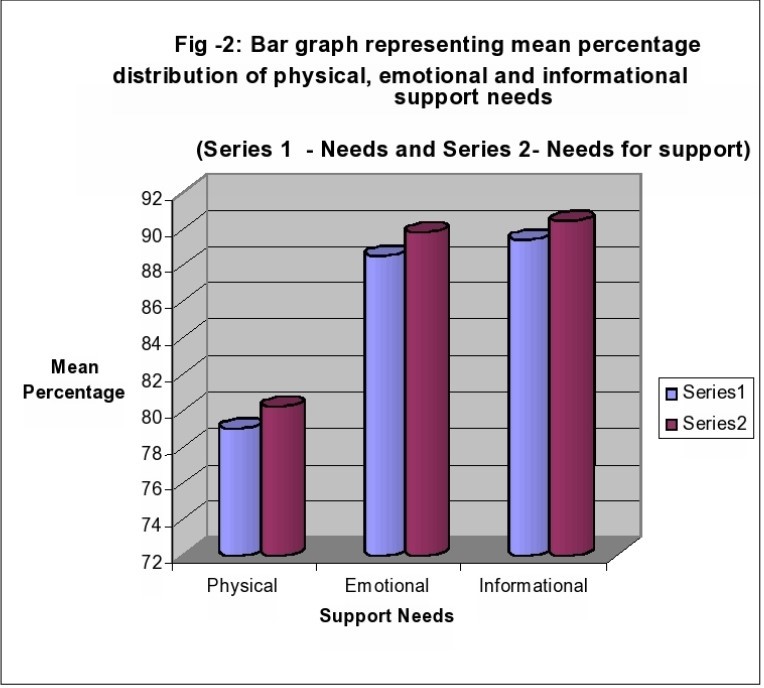

Overall findings showed that the mean percentage distribution of scores were highest in needs (89.4%) and need for support (90.33%) in the informational support category and lowest in needs (79%) and need for support (80.19%) in the physical support category (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.Bar graph representing mean percentage distribution of physical, emotional and informational support needs (Series 1 - Needs and Series 2- Needs for support)

Women in labour have needs related to physical, emotional and informational support. Informational and emotional support needs are perceived to be greater than physical support.

On further analysis to determine perspectives of needs and need for support among primigravida and multigravida , it was found that multigravida with past experience of labour appeared to have a lesser need for support in physical, emotional and informational support category compared to primigravida and multigravida with no past experience of labour (Table 5).

For primigravid women, and multiparous women who were experiencing labour for the first time, the ‘need for support’ scores in all three aspects of support, physical, emotional and informational, were more than or equal to the ‘need’ score indicating that they needed more support to meet their needs compared to women who had previous experience of labour.

Table 5. Mean percentage distribution of scores among primigravida and multigravida under physical, emotional and informational support (n=60: primigravida – 44, multigravida with past experience of labour – 10 and multigravida with no experience of labour – 6).| Support Needs Max score per woman | Mean percentage distribution of scores | ||||||

| Primigravida (n=44) | Multigravida with past experience of labour (n=10) | Multigravida with no experience of labour (n=6) | |||||

| Need | Need for support | Need | Need for support | Need | Need for support | ||

| Physical | 27 | 81.33 | 83.33 | 74.10 | 68.89 | 71.60 | 81.49 |

| Emotional | 18 | 88.00 | 89.28 | 87.22 | 84.44 | 85.17 | 92.61 |

| Informational | 15 | 89.67 | 89.67 | 86.67 | 86.67 | 92.20 | 94.47 |

Discussion

Labour and childbirth being the most crucial moment of a woman's life, her perceived expectations play a significant role in determining the measures to make it a positive and more satisfying experience for herself and her family. This study is valuable due to its contribution to literature that describes the support measures expected and perceived by women from their care provider or support person. Findings of the study have identified that Indian women perceived labour support needs in the informational and emotional support categories as more helpful and important than those in the physical support category. These findings have been supported by researchers from previous studies conducted in North Carolina, Mid-Western USA and Canada on nulliparous women's perspectives about their nurse’s role during labour and delivery and reported that the majority of support measures were related to providing physical comfort, emotional support and informational support and some related to providing technical nursing care.9, 10, 11

A systematic review of 137 reports, which included descriptive studies, randomised control trials and systematic reviews of intrapartum interventions, has elaborated women's evaluation of their childbirth experiences. The four important factors highlighted were: expectations of the labouring women, type and quality of support received from care givers, interpersonal relationship of care giver to the labouring women and involvement of the women in decision-making regarding their own care.12These findings are in line with the current study findings, where participants have perceived and valued informational and emotional support as more significant than physical support in labour. However, the findings of the study are in contrast to results of an investigation of 120 women's perceptions of midwifery support in labour, which indicated that women in Africa perceived emotional support as more helpful than informational support.13 Although the current study findings present that women in labour felt informational support (90.33%) as more important than emotional support (88.78%) and physical support (80.19), the difference is very minimal.

The quantitative and qualitative findings from a cross-sectional study exploring midwives' caring and supporting behaviours in a public and private hospital in Tanzania, which compared nurses’ and midwives' caring and supporting behaviours suggested that women from the public hospital perceived that they received more emotional support than women from the private hospital, who expressed that they received more informational support. The qualitative findings from four focus group discussions (two with primiparas and two with multiparas with six participants in each focus group) identified two major themes: ‘presence of a care giver’ and ‘listening to the labouring women’. Encouragement was valued by all the women as an important aspect of their care.14This is in line with the findings of the current research where ‘reassurance’ (100%) and ‘encouragement’ (100%) were perceived as helpful and supportive by all women.

Further research into supporting women in labour from the perspectives of midwives, women and partners provide different concepts to labour support. Midwives' perception of being a professional support focused mainly on providing the woman with a sense of security through information sharing and helping her to be in control, whereas partners’ and women’s expectations focussed on presence of the midwife to provide continuous support during labour.15Non-pharmacological measures for pain relief, such as supporting the woman with physical support measures (through positioning, mobilisation, hydration, elimination and hygiene), emotional support (through reassurance, attention focussing, distraction and encouragement) and informational support (through information sharing and advice) during labour have all been reported to be helpful and supportive by women in early labour in the current study. There is strong evidence agreeing with these findings, whereby non-pharmacological approaches of pain relief, such as relaxation techniques, massage, water immersion, ambulation and positioning with continuous support during labour when used as primary approaches for pain relief have been reported to be associated with greater maternal satisfaction and better outcomes of labour.16, 17, 18

Regardless of the type and quality of support, it is seen in most of the studies that women in labour value the presence of a care giver throughout labour who can understand, encourage and involve the woman in her own care, respecting her identity. Given that many modern maternity units are under-staffed and women in labour feel unsupported and alone in both Ireland19and the UK20, these findings are of great importance to guide future care. A review summary from 22 trials involving 15,288 women from 16 countries has reported continuous one-to-one support in labour to be associated with better labour outcomes in terms of more spontaneous vaginal births, reduced need for analgesia, shortened duration of labour and better neonatal outcomes.21

This was a small study, in only four maternity units in India; the findings, therefore, are not necessarily generalisable to other countries or cultures. However, the fact that the results have been supported by many studies worldwide indicates that the findings could be applicable in other area. Overall, the aim of supporting women in labour is to make labour the most satisfying experience for a woman and improving the outcomes for the mother and baby. This not only has implications for the child bearing woman and her family, but also plays a significant role in determining the quality of care provided by the health professional and the organisation.

The findings of the study have several implications for evidence-based midwifery or maternity nursing practice, education, administration and research. One of the significant findings suggested that the presence of a support person throughout labour is an important aspect in caring for women in labour. These findings would help maternity care administrators to understand the significance of one-to-one care and maternity ward/labour ward staffing could be improved to provide comprehensive care to women in labour. A joint commission with collaboration from four organisations (the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, the American College of Nurse-Midwives and the Society of Maternal-Foetal Medicine) have placed a greater emphasis on some barriers in provision of intrapartum care and measures to improve them. It has indicated that understaffing and lack of effective communication and leadership in organisations are some of the common barriers in intrapartum care and placing focus on improving these can improve the outcome.22

The study findings can also be of help to future nurse/midwife researchers to carry out further studies in determining the support needs in different stages of labour as well as to study the constraints or barriers in providing need-based care to women in labour and the different possible ways to overcome the barriers and constraints. These findings can be useful in teaching students in the field of maternity nursing and early practitioners about the significance of understanding women’s expectations from their care providers, with an ultimate goal to make labour a satisfying experience for the women they care for and improving their labour outcomes through emphasis on use of evidence based practice.

Conclusion

Making labour a memorable and positive experience for women is the goal of every organisation. The study findings conclude that women in labour have support needs related to physical, emotional and informational support regardless of their parity. However, the support needs perceived by women experiencing labour for the first time were found to be greater than those who had already experienced labour before. Support needs in the informational and emotional category were more than those in the physical category, which does suggest that the presence of an experienced and empathic care provider is of vital importance. Care providers not only have a role to provide physical comfort to the woman to help her cope with labour pain but also to provide emotional support and necessary information during the process of labour. Care guidelines based on evidence and documented needs of women in labour will ultimately make labour experience a memorable one for women and their families.

Study findings will help care providers to understand labouring women’s support needs, hence making labour a more satisfying experience for the woman and her family.

Conflict of interest

The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of the manuscript.

Ethics

The study was conducted as part of fulfilment of a Master’s Degree in Maternity Nursing. Permission was obtained from the head of the institutions and ethical committees of the primary institution and the selected study sites, and informed verbal consent was obtained from the participants of the study prior to data collection.

Acknowledgements

This was a self-funded study as part of the Master's Programme in Maternity Nursing and the author would like to acknowledge the faculty of the College of Nursing, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka and the four study sites, Kasturba hospital, Dr. TMA Pai Hospital, Lombard Memorial Hospital and the Sonia Clinic for granting permission and facilitating the conduct of this research and for the continued support during the period of the study. The author would like extend heartfelt gratitude to the supervisors for their guidance and support for the conduct of the research and during the course of study. The author also would like to acknowledge and extend sincere gratitude to the participants of the pilot study and the main study for their contribution during the period of data collection. The author would like to acknowledge the current employer, the Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital, Dolphins Barn, Dublin-8, Ireland for facilitating the author to utilise components of evidence based practice in day-to-day midwifery care.

References

- 1.Smith L F. (2001) Development of a multidimensional labour satisfaction questionnaire: dimensions, validity, and internal reliability. Quality in Health Care. 10(1), 17-22.

- 2.Sleutel M R. (2003) Intrapartum nursing: Integrating Ruben’s Framework With Social Support Theory. , Journal of Obstetrics, Gynacology and Neonatal Nursing 32(1), 76-82.

- 3.Corbett C A, Callister L C. (2000) Nursing Support During Labour. , Clinical Nursing Research 9(1), 70-83.

- 4.Manogin T W, Bechtel G A, Rami J S. (2000) Caring Behaviours By Nurses: Women’s Perceptions During Child Birth. , Journal of Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Neonatal Nursing 29(2), 153-157.

- 5.Chen C H, Wang S Y, Chang M Y. (2001) Women’s Perceptions of Helpful and Unhelpful Nursing Behaviours During Labour: A Study in Taiwan. , Birth 28(3), 180-185.

- 6.Ip W Y, Chien W T, Cl Chan. (2003) Child Birth expectations of Chinese First-Time Pregnant Women. , Journal of Advanced Nursing 42(2), 151-158.

- 7.Miltner R S. (2000) Identifying Labour Support Actions of Intrapartum Nurses. , Journal of Obstetrics, Gynacology and Neonatal Nursing 29(5), 491-499.

- 8.Mosallam M, Rizk D E, Thomas L, Ezimokhai M. (2004) Women’s attitudes towards psychosocial support in labour in United Arab Emirates. , Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 269(3), 181-187.

- 9.Tumbin A, Simkin P. (2001) Pregnant Women's Perceptions of Their Nurses' Role During Labour and Delivery. , Birth 28(1), 52-56.

- 10.Braynton J, Fraser-Davey H, Sullivan P. (1994) Women’s Perceptions of Nursing Support During Labour. , Journal of Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Neonatal Nursing 23(8), 638-644.

- 11.Gilliland A L. (2011) After praise and encouragement: emotional support strategies used by birth doulas in the USA and Canada. , Midwifery 27(4), 525-531.

- 12.Hodnett E. (2002) Pain and Women’s Satisfaction with the Experience of Child Birth: A Systematic Review. , American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 186(5), 160-172.

- 13.Mybe M, Tsay S, Kao C, Lin K. (2011) Perceptions of Midwife support During Labour and Delivery in Gambia. , African Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health 5(2), 59-66.

- 14.Eustace R W, Lugina H I. (2007) Mother's Perceptions of Midwives’ Labour and Delivery Support. , African Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health 1(1), 5-9.

- 15.Thorstensson S, Ekstrom A, Lundgren I, Wahn E H. (2012) Exploring Professional Support Offered by Midwives during Labour: An Observation and Interview Study.” Nurse Research and Practice:. 648405.

- 16.Chaillet N, Belaid L, Crochetiere C, Roy L, Gagne G. (2014) Nonpharmacologic Approaches for Pain Management During Labor Compared with Usual Care: A Meta-Analysis. , Birth 41(2), 122-136.

- 17.C A Smith, Levett K M, Collins C T, Crowther C A. (2011) Relaxation techniques for pain management in labour." Cochrane Database Systematic Review (12): Cd009514.

- 18.C A Smith, K M Levett, C T, Jones L. (2012) Massage, reflexology and other manual methods for pain management in labour.” Cochrane Database Systematic Review 2: Cd009290.

- 19.Larkin P, C M Begley, Devane D. (2012) Not enough people to look after you’: An exploration of women’s experiences of childbirth in the Republic of Ireland. , Midwifery 28(1), 98-105.

- 20.McInnes R J, McIntosh C. (2012) What future for midwifery? Nurse Education in Practice. 12(5), 297-300.

Cited by (1)

- 1.Sharma Preetika, Bagga Rashmi, Khan Maliha, Duggal Mona, Hosapatna Basavarajappa Darshan, et al, 2025, Maternal health education and social support needs across the perinatal continuum of care: a thematic analysis of interviews with postpartum women in Punjab, India, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 25(1), 10.1186/s12884-025-07813-8